What Are Perfume Notes?

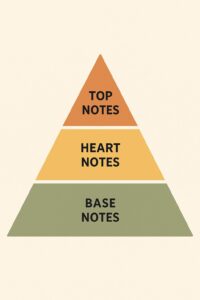

Welcome, my brothers and sisters in fragrance! How do you describe that scent? Some people prefer using imagery to describe their scent as a citrus cocktail at first, then mellows into a floral bouquet, and finally clings to you like a warm, woody hug hours later. That’s 100% me. That is the magic of perfume. And now, with this guide, I’m going to discuss the perfume notes that make up a fragrance and help you beef up those descriptions. A fragrance is essentially a three-act play: Top Notes (the opening act that grabs your attention and then dips out), Heart Notes (the main storyline that develops once the notes of the top have exited stage-right), and Base Notes (the grand finale that stays with you until the end). In this guide, I will break down the most notable notes in each category – top, heart, and base – complete with vivid descriptions, some history, cultural lore, and examples of famous perfumes where each note takes center stage. Let’s dive nose-first into the world of perfume notes!

Top Notes – First Impressions and Fast Exits

Top notes are the attention grabbers of a fragrance. These are the bright and volatile scents that hit your nose right after spraying and often times don’t last long. Top notes are usually light, fresh, and uplifting – think zesty citrus, crisp herbs, or airy aldehydes – and they evaporate quickly, making way for the heart notes typically within 5 to 20 minutes. As these are often just the first impression of a fragrance, don’t get too attached to them. Too often, when smelling on a strip, I’ve thought that I hated something but after wearing it on the skin, my opinion eventually changes after an hour. Top notes are fleeting but play an important role as they set the stage. Here are some of the most iconic top notes:

Bergamot

Bergamot is everywhere. This little green citrus (a hybrid of lemon and bitter orange) is the quintessential top note and in fact, it’s often cited as the most prevalent ingredient in top-note blends. You’ll notice the sunny citrus peel with a subtle floral undertone, existing as the cheerful Italian extrovert of the perfume world. It introduces itself and then, true to top-note form, bows out gracefully before you’ve finished your coffee. Historically, bergamot gained fame not just in perfume but in tea as the scent that gives Earl Grey tea its signature aroma. Its why you often times see Bergamot as a top note in tea-based fragrances such as Wulong Cha from Nishane. Culturally, bergamot oil has been used in Italian folk medicine and to flavor confectionery, but in perfumery it’s basically everywhere – from classic 18th-century Eau de Cologne formulas to modern designer hits. Guerlain Shalimar (1925) uses bergamot in its top to give a lemony spark before the vanilla kicks in while Tom Ford’s Neroli Portofino opens with a bright blast of bergamot that practically screams Mediterranean seaside. If a fragrance’s first sniff feels like a sunny, energetic hello that seemingly fades too fast, then you can be sure that that’s bergamot doing its job.

Lemon

Sharp, clean, and unapologetically citrusy, lemon in a top note wakes up your senses in the best way. It smells exactly as you’d imagine – like the rind of a fresh lemon, bursting with sour yellow goodness and it’s often used to give fragrances a bright, clean opening. Historically, lemon has been a staple since the original Eau de Cologne recipes circa 1709. In cultural terms, we’ve long associated lemon with cleanliness and energy which explains why your kitchen cleaner is lemon-scented. In perfumery, lemon can be a bit linear and short-lived, but it always leaves a mark. Classic examples include Dior Eau Sauvage (1966), which greets you with a dazzling lemon and is still sold today, and Dolce & Gabbana Light Blue (2001) where Sicilian lemon gives that Italy vacation vibe right off the bat. Lemon is often paired with other citrus or herbs to form that archetypal “fresh” accord; blink and you’ll miss it, but while it’s there you’ll appreciate it. Just don’t be surprised when it evaporates before you get a chance to really sit in it.

Aldehydes

If you’ve never heard of them, aldehydes can sound a bit clinical or scary. However, chances are that you’ve likely smelled them in some of the most glamorous perfumes without even realizing. Aldehydes are synthetic notes (basically lab-created molecules) that, when used in perfumery, give off a champagne-like sparkle. Imagine the smell of bubbles or a freshly struck match mixed with clean linen – that’s the vibe of classic aldehydes. The most famous example? Easily Chanel No. 5 (1921), the grand dame of aldehydic florals. When No.5 first hit the scene, its overdose of aldehydes made it smell like nothing else at the time – it had a “sparkle” and soapiness that screamed flowery high-class. Legend has it that the perfumer Ernest Beaux mistakenly or purposefully added a dose far above the norm, giving Chanel No.5 its signature aura that has continued to inspire flankers to this day. Wearing an aldehydic fragrance was practically a status symbol for the elegant post-war woman. It’s the olfactory equivalent of a little black dress with a fabulous diamond necklace.

Neroli

Fresh and floral, this lovely note comes from the delicate white flowers of the bitter orange tree and it smells like a fresh floral with a citrusy kick. Imagine orange blossoms in a spring breeze, green and bright yet softly sweet. Neroli is often found in those refreshing “eau de cologne” type scents, imparting an instantly recognizable soapy, honeyed-floral freshness. Neroli got its name from an actual 17th-century Italian trendsetter: Anne Marie Orsini, the Princess of Nerola, who was so obsessed with the scent that she used it to perfume her gloves and bath, sparking a fad. Ever since, “neroli” has been the perfumery term for this essence. In perfumery, neroli shines in classics like 4711 Cologne and modern hits like the already-mentioned Tom Ford Neroli Portofino. Another gorgeous example: Guerlain Eau de Cologne Impériale (1853), reportedly created for Empress Eugénie. In short, neroli is an uplifting, shampoo-fresh floral note that has been known to lift the spirits of many.

Mint (Peppermint)

One of my favorite notes, mint instantly makes me feel on top of the world. I know its late but the first time a mint note REALLY stood out to me was in Amouage Enclave. I ordered a sample just based off of what I heard and I was left stunned at how fresh while soothing the mint not is. Peppermint as a top note brings a cooling, tingly effect that can wake up a fragrance composition. The smell? Its a fresh mint leaf: it’s herbal, green, a tad sweet, and has that unmistakable mentholated icy kick. As a fan of icy scents (see Gentle Fluidity Silver by Maison Français Kurkdijan), I couldn’t resist Enclave (and how much it reminded me of a mojito) and it has lead me on a hunt for other icy scents ever since. As a perfume note, mint has been used creatively in both feminine and masculine scents to give an energetic, sporty twist. Notable example: Guerlain Aqua Allegoria Herba Fresca (1999) which literally smells like a dewy garden with heaps of mint and grass and Cartier Roadster (2008), which built a whole concept around a chilly mint note over woods and patchouli, giving a modern masculine vibe. Historically, mint’s not a super old-school perfume ingredient, but culturally, mint has always signified cleanliness and vitality (the ancient Greeks and Romans were big on mint in baths and medicine). So when a modern perfumer wants to shout “fresh and dynamic!” in the opening, they toss in some mint. Just be warned: too much mint and you risk smelling like you accidentally sprayed mouthwash – the line between innovative and dentist’s office is a fine one that I wonder if I’m crossing each and every time I use a mint-based scent. Used right, though, mint is a zingy delight that might surprise even the most virgin nose.

“Marine” Aquatic Notes (Calone)

Ever worn a ’90s cologne and immediately thought of the ocean? You can thank Calone and its aquatic and synthetic notes that practically defined an era. Marine/aquatic notes are those that evoke sea spray, salty air, or the vibe of dark ocean. Calone in particular is an aroma molecule discovered in the 1960s, smelling oddly like a mix of fresh sea air and melon. In the top of a fragrance, it gives a distinctive “cool water” accord – at once watery, slightly sweet, and airy. The cultural explosion of these notes hit in late ’80s and ’90s: Davidoff Cool Water (1988) was a trailblazer that made everyone want to smell like a freshly showered lifeguard. Its also one of the first fragrances I remember hearing about. As much as I’ve never been able to appreciate it, Issey Miyake L’Eau d’Issey (1992) put a marine, dewy spin on florals for women. Suddenly, everything became “oceanic” and “fresh.” While some connoisseurs roll their eyes at aquatics now (yes, they were that overdone for a while), there’s no denying marine notes created some legends and are still used when a perfumer wants to convey “blue skies, open waters, carefree vibes.” Just look at effect Bleu de Chanel (2010) has had on the industry. As much as I adored the eau de toilette, the parfum is even better and deeper.

Heart Notes – The Plot Thickens

Once the flashy top notes start to fade away, heart notes begin to take over and for me, this is where you get real personality of a perfume. Heart (or middle) notes form the core of the fragrance, typically emerging after the first 15 minutes and lasting a good hour or more as the main attraction of the scent. They are often fuller and more complex aromas that give a perfume its identity and emotional vibe. As the top notes evaporate, heart notes bloom while giving a preview of the base. Let’s explore some typical notes that have made up the heart notes of many legendary fragrances.

Rose

The classic and always romantic rose is possibly the most iconic heart note of all time. If you’ve smelled more than 3 fragrances in your life, chances are you’ve encountered rose in some form. In scent, rose notes can range from fresh and dewy to rich and jammy, or even dark and spicy. I wear L’homme à la rose from MFK, Santal Royal from Guerlain and Rock Rose from Clive Christian and they all feel like 3 different roses. It’s incredibly versatile. Historically, rose has pedigree: it’s been used in perfumes and attars for millennia (Cleopatra and the ancient Persians were basically bathing in rose oil). By the end of the 19th century, rose-centric perfumes were all the rage in Europe – a symbol of femininity and luxury. In modern perfumery, rose can be traditional or punky – for example, Paul Smith Rose (a straightforward fresh rose soliflore), Serge Lutens La Fille de Berlin (a bold, thorny, spicy rose that is as edgy as its name suggests), or Chloé Eau de Parfum (2008, that airy lychee-rose that became a bestseller). There’s also Le Labo Rose 31, which pairs rose with cumin and woods to make it unisex and mysterious. Rose is everywhere: it’s in classics like Guerlain Nahema or Yves Saint Laurent Paris, and a supporting actress in tons of others where you might not even realize it.

Jasmine

On one hand, jasmine smells heavenly: a rich, sweet white floral that’s heady and nectar-like, evoking warm summer nights and sensual exotic gardens. On the other hand, real jasmine has a hint of funk. That funk is precisely what gives jasmine its full-bodied, carnal gorgeousness in perfume. Historically, jasmine has been prized in perfumery for ages, harvested at night when its scent is strongest. In India, jasmine garlands are used in weddings and spiritual ceremonies (it’s a symbol of love and divine hope). In the West, jasmine gained fame as a key ingredient in legendary perfumes: Joy by Jean Patou (1930) famously poured an extravagant amount of jasmine and rose – marketing it as “the costliest perfume in the world” back then. And of course, Chanel No. 5 has a hefty dose of jasmine from Grasse that gives it that creamy floral heart beyond the aldehydes. Culturally, jasmine often signifies beauty and sensuality and it’s that note in a perfume that can make the blend feel luxurious and a bit flirty. Modern jasmines worth noting: Dior J’adore (a radiant, clean jasmine mix), Serge Lutens A La Nuit (a hardcore jasmine soliflore – like 8000 jasmine flowers smacking you in the face at once, truly for enthusiasts), and Mugler Alien (jasmine sambac amped up to extraterrestrial levels, paired with amber). When you catch a whiff of jasmine, you might imagine an evening garden under the moonlight. Either way, jasmine will always make you feel like a million bucks when it shines through.

Ylang-Ylang

Pronounced “ee-lang ee-lang,” this tropical note is a perfume note often found in aromatherapy that blends well with floral and woody scents. Ylang-ylang comes from the yellow star-shaped flowers of the Cananga tree, native to Southeast Asia, and its scent is a heady mix of creamy, sweet floral with a banana-like and custardy richness. Historically, the essential oil of ylang-ylang was a key ingredient in Victorian-era Macassar hair oil (gentlemen in the 19th century would grease their magnificent mustaches and manes with ylang-ylang infused oil ). It was also first distilled around 1860 in Manila; by the late 19th century, the “flower of flowers” had made its way into European perfumery big time. Perhaps most famously, ylang-ylang is part of the legendary bouquet in Chanel No. 5, contributing to that ultra-feminine heart along with rose and jasmine. In modern perfumery, ylang-ylang is featured in scents like Estée Lauder’s Beautiful and Dior J’Adore (bringing that lush tropical white-flower tone), or Guerlain’s classic Chamade where it’s beautifully green and pollen-like. Ylang can be loud, so perfumers often “tame” it by blending with lighter florals or citrus. It’s that note that makes a fragrance feel like it’s got a sultry, tropical soul and gives it a bit of an edge.

Tuberose

This white flower (despite “rose” in the name, it’s unrelated) smells opulent, lush, and a really carnal. We’re talking creamy floral sweetness with facets of buttery, indolic, almost coconut-like richness, and a noticeable camphoraceous (menthol-ish) edge that gives it a polarizing quality. In perfumery, tuberose is behind some of the most infamous “big” florals, for example Fracas by Robert Piguet (1948) – a legendary tuberose bombshell that announced “I’m in the building and I’m glamorous” from half a mile away. Modern iterations include Frederic Malle Carnal Flower (2005, a more mentholated, airy green tuberose), and Mugler Aura where tuberose meets greens and vanilla in a futuristic combo. That being said, in the right dosage, tuberose can add a creamy depth and tropical vibe to more demure blends. One bloom of tuberose can fill a whole room with scent – likewise one drop too many in a perfume can fill an elevator for hours. Handle with care.

Violet

Violet is a tale of two scents: the violet flower and the violet leaf. The flower note (often created with ionones, synthetic violet aroma molecules discovered in the late 19th century) smells powdery, sweet, and slightly candied. It’s the smell of old-fashioned lipstick kisses and Victorian parlors (violet perfumes were hugely popular in the late 1800s; even famous perfume house Guerlain had “Violet” creations). On the other hand, violet leaf smells green, dewy, and cucumber-like with an ozonic twist. Both are used in perfumery, often to very different effect. Violet flower notes in the heart can lend a romantic, nostalgic feel – think Balenciaga Paris (2010) which wraps a soft violet in woods and modern chic, or Penhaligon’s Violetta, a pretty soliflore that smells like a posh English garden party circa 1920. Meanwhile, violet leaf is key in many masculine or unisex scents for a fresh, almost aquatic-green touch: Grey Flannel by Geoffrey Beene (1975) is a classic men’s fragrance absolutely drenched in green violet leaf – it’s like sniffing a freshly crushed leaf with a tinge of floral. And Dior Fahrenheit (1988) brilliantly pairs violet leaf’s petrol-like green note with leather, giving that famous “gasoline violet” vibe. Historically, violets were so adored that Toulouse in France became known for its violet farms and perfumes. Culturally, violets symbolize modesty and fidelity. But in perfume, violet can be demure or surprisingly edgy. The heart note of violet (especially the candied floral part) often gives perfumes a vintage, powdery charm – think Guerlain’s Après L’Ondée (1906) which combines violet, iris and heliotrope in melancholic beauty. Whenever you catch a whiff of something that smells like plush powder puffs or a bouquet in an antique vase – that’s violet making its shy yet unmistakable presence known.

Iris (Orris)

Iris in perfumery is the definition of understated luxury. Now, to be clear, when I say “iris” as a note, we typically mean the scent from orris root – the aged rhizomes of the iris plant – not really the fresh floral scent of iris blooms. Orris root yields an aroma that’s powdery, cool, and elegant, often compared to the smell of violet (they share some molecules) but with a woody, starchy, even slightly bread-and-carrot-like nuance. That may sound odd, but in a perfume’s heart, iris note translates to a plush, powdery, almost buttery smoothness that gives an instant aura of class while sometimes giving a lipstick smell. It’s also one of the most expensive ingredients – by weight, high-quality orris butter can cost upwards of $50,000 per kilogram. Why so pricey? Because it takes years of growing, then years of drying and aging the roots to develop the desired irones (scent molecules), and only then can it be extracted! Historically, iris root has been used as a cosmetic powder and fragrance since ancient times. In the 18th century, it was used to scent wigs and clothes. But its star turn came in classical perfumes such Chanel No. 19 (1971), which features a stunning iris heart (blended with rose and green galbanum) to give a chilly, aristocratic vibe, or Guerlain L’Heure Bleue (1912) where iris adds to the melancholic powdery twilight feel. Fast-forward to the modern age and iris has become most known perhaps as the “luxury” note in Dior Homme (original 2005 version), which famously has a gorgeous iris that smells like expensive lipstick (in a sexy man’s fragrance, breaking all gender rules, and it’s fabulous). Prada Infusion d’Iris (2007) is a minimalist’s dream – it smells like clean, light iris water, very zen. Personally, I wear Harmonious from Boadicea the Victorious as well as Givenchy Gentleman Réserve Privée when I need my iris fix and want to turn heads. It’s both retro and futuristic, delicate and strong, ghostly and comforting.

Lavender

As a heart note (and sometimes a top note), lavender brings a familiar, aromatic herbal quality: it’s fresh, camphoraceous (that slightly medicinal cooling note), with a soft floral undertone and a pleasant bitterness like a summer meadow. Lavender is soothing, yet invigorating. Historically, lavender’s use dates back to Roman times for bathing (the Latin “lavare” means to wash – yes, the Romans basically named it after its use as a bath scent). It’s been the cornerstone of fougère fragrances since 1882 when Houbigant’s Fougère Royale basically invented modern men’s perfumery by mixing lavender with coumarin (tonka). That combo of lavender-fern-like aroma with sweet coumarin and oakmoss defined the “barbershop” genre. While most men crossed that barrier with Chanel’s Platinum Égoïste, my welcome was Tom Ford’s Beau du Jour, a more modern take on a fougère. In culture, lavender has long been associated with calmness (how many sleep aromatherapy products are lavender-scented?). It also got a reputation as a bit “old-fashioned” because of its use in linen sachets and cleaning products. But perfumers keep reinventing it. For instance, Yves Saint Laurent Opium pour Homme (1995) did a spicy oriental take with lavender; Mugler AMen* (1996) tossed a streak of lavender into a coffee-patchouli party; and Jean-Paul Gaultier’s Le Male (1995) amped the minty side of lavender with vanilla for a sweet twist that became iconic. And then there’s Maison Francis Kurkdjian’s Masculin Pluriel or Tom Ford’s Lavender Extreme, showing lavender can be uber-sophisticated or intense. When you smell lavender in a heart note, often it’s paired with geranium or woods to create that suave, aromatic heart. But lavender isn’t just for the gents – Guerlain’s Jicky (1889) was technically unisex, using lavender, vanilla, and civet (and legend has it even women wore it daringly), and Tom Ford’s Lavande Triomphante is a lush take anyone can rock. Lavender in the heart gives a fragrance a confident, uplifting cleanliness, but with more depth than a simple citrus.

Cinnamon

Spicy, warm, and a little sweet – cinnamon is the note that can turn a bland perfume into a cozy, exotic concoction. For me, the premier cinnamon fragrance is Musc Ravageur by Frédéric Malle. Whenever I wear this one, I feel like the sexiest person in the room. As a heart note, cinnamon adds a warm spice that is instantly recognizable. It has a fiery kick but also a gourmand appeal it’s nuance is prevalent when done right. Historically, cinnamon has been valued since antiquity – it was part of the spice trade that basically drove world exploration (people literally crossed oceans in search of stuff like cinnamon bark!). In perfumery, it pops up a lot in what we call “oriental” fragrances (a perhaps outdated term, but it refers to perfumes with rich spices, resins and vanilla). Take Yves Saint Laurent Opium (1977) – a legendary spicy oriental where cinnamon, clove, and myrrh whirl around a deep balsamic base; it’s as if the spice market of your dreams exploded in a bottle. More modern: Hermès Ambre Narguilé (2004) uses cinnamon to create a delicious pipe tobacco/apple pie vibe, like lounging in a hookah lounge that serves dessert. And who could forget Viktor & Rolf Spicebomb (2012) – cinnamon is one of the big players there, giving that cologne its sweet-hot kick among tobacco, leather, and chili. Culturally, cinnamon is associated with warmth, holidays, and a bit of exotic flair. When you smell a perfume with a cinnamon heart, it often feels like a comforting hug or a sensual embrace depending on what it’s paired with. Just a touch can add sparkle and warmth; too much and you risk smelling like a Yankee Candle. But balanced well, cinnamon can present itself as the note that you always remember about a fragrance.

Cardamom

Cardamom is the cool, suave spice that’s gives a kick to your fragrances. Where cinnamon is hot and straightforward, cardamom is cooler, subtly sweet, and intriguingly complex. It smells aromatic and green-spicy like a zesty, slightly mentholated mix of eucalyptus, ginger, and pepper, with a lemony undertone. If you’ve had chai tea or Swedish cardamom buns, you know cardamom. In perfumes, cardamom can do wonders by adding a refined, almost exotic freshness to the heart. It’s widely used in both men’s and women’s scents, often bridging the gap between citrusy top and woodsy base with its aromatic charm. A notable example: Jean Paul Gaultier Le Male has a hint of cardamom in its heart (though mint and lavender steal the show), adding to that scrumptious warmth. But the real modern cardamom classic is Yves Saint Laurent La Nuit de L’Homme (2009) – basically a cardamom bomb in the opening and heart. That fragrance got so many compliments it practically became every guy’s go-to date night scent for a decade. I know I personally wore it to nightclubs all across the southeast. The cardamom there is uber-sexy, giving a dark, sparkling spice atop cedar and coumarin. Culturally, in Middle Eastern and South Asian countries, cardamom’s used to scent coffee and desserts – a sign of hospitality and luxury. In a perfume’s heart, cardamom often reads as sophisticated and cosmopolitan. It’s the note that can make a fragrance feel modern or slightly unconventional, without scaring anyone off.

Base Notes – The Grand Finale

The final act of a fragrance. Base notes are the heavy hitters that stick around long after the other notes have left the building. They emerge slowly as the perfume dries down, supporting the top and heart notes, and then taking center stage in the scent’s final hours. Base notes are typically rich, deep aromas: woods, resins, balsams, musks, and gourmand notes that provide warmth and longevity. Base notes also often determine whether you still love a perfume at the end of the day. Let’s explore some base notes that you should know.

Sandalwood

Soft, creamy, woody – sandalwood is like the zen master of base notes. It’s a precious wood (traditionally from the Mysore region of India) that smells milky, smooth, and slightly sweet, with a subtle, lingering sensuality. Imagine the scent of a wooden temple or an old wooden chest that’s buttery and rich rather than rough or pencil-shaving-like – that’s sandalwood. Historically, Mysore sandalwood was so prized it became endangered from overharvesting. So much so that the Indian government had to step in with controls, and since the 1990s genuine Mysore sandalwood oil became rare and extremely costly. Now, a lot of what we call “sandalwood” in perfumes is either Australian sandalwood (a slightly drier cousin) or synthetic recreations that mimic that creamy warmth. In perfumery, sandalwood can make a fragrance feel luxurious and grounding. Take Guerlain Samsara (1989), which was built around a huge dose of sandalwood – it wraps you in a lush, meditative wood hug. Or Le Labo Santal 33 (2011), the hipster runaway hit in New York City that drenched everyone in a dry, smoky sandalwood leather aura for the past decade. Sandalwood is also in classics like Chanel Bois des Iles (1926), one of the first woody perfumes for women. The beauty of sandalwood as a base is that it’s both persistent and mellow. It pairs beautifully with florals, vanillas, resins… you name it. When a perfume dries down and you feel like you’re enveloped in a smooth, slightly woody creaminess that almost feels like skin but better, you can bet sandalwood is in the mix.

Cedarwood

If sandalwood is creamy, cedarwood is boldly dry. Cedar is that pencil shavings, freshly sharpened wood smell. Crisp and a bit aromatic, cedar has natural cedar-oil which reminds of turpentine in a pleasant way. It’s often described as smelling like a new wooden cigar box. In perfumery, cedarwood is a backbone base note, especially in masculine scents. It gives that dry, straight-wood, no-sweetness anchor. Think Terre d’Hermès (2006) – a masterpiece of vetiver and cedar from Hermès that feels like standing on a rocky cliff; the cedar there is mineralic and rugged. Or older classics like Déclaration by Cartier (1998), which features a prominent spicy cedar note, making it elegantly masculine and a tad cerebral. Cedar plays nice with practically everything: it can prop up citrus to make a “cologne” last longer (e.g., Atelier Cologne’s Cedrat Enivrant uses cedar in the base under lemon), or bolster florals to give them unisex appeal (many modern florals have cedar or iso-E Super – a synthetic cedar-like molecule – to add a clean wood structure). It’s also the main player in the ever-popular “white woods” accord of many contemporary perfumes, which gives that smooth Ikea-furniture-assembly vibe (I joke, but actually many love that vibe). Culturally, cedarwood signals reliability and natural simplicity. It’s not as sensual as sandalwood or as dark as some other woods, but it’s unfussy, classic, and incredibly versatile.

Vetiver

Earthy, smoky, and intriguingly green-brown, vetiver is the root of an Indian grass (Chrysopogon zizanioides) and a mainstay of perfumery’s base note roster. If you’ve never smelled vetiver, imagine pulling up clumps of grass from damp soil – it’s grassy but also dirt-like, with a dry smoky finish, almost like pencil shavings or smoky tea at times. Vetiver has a complex profile: depending on origin, it can be more clean and green (Haitian vetiver is lighter, fresher) or dark and smoky (Javanese vetiver is pungent and inky). Historically, vetiver has been used in tropical countries for cooling: woven into mats or fans, it gives a pleasant scent. It’s been in perfumery at least since the 1800s, often in men’s colognes and fougères for that dry elegant touch. The quintessential vetiver fragrance is appropriately named Guerlain Vetiver (originally 1950s, reformulated 1961) – it set the gold standard for a classic gentleman’s vetiver: very green, dry, with tobacco and nutmeg touches. Another to check: Chanel Sycomore, part of their Les Exclusifs, which gives a rich, slightly sweet and woodsy vetiver that smells like expensive boots walking through a forest. On the niche side, Lalique Encre Noire (2006) celebrated vetiver’s dark side – inky, mysterious, and shockingly affordable to boot. In my personal collection, I wear Vetiver Extroadinaire by Frédéric Malle (2002) when I want feel like I’m getting some real work done. Vetiver often appears in unisex and women’s perfumes too, especially modern ones aiming for a chic, minimalist vibe – e.g., Hermès Jardin series or Jo Malone’s Vetiver & Golden Vanilla that pairs smoky vetiver with vanilla. Culturally, vetiver is sometimes associated with durability. As a base note, vetiver adds terrific longevity and a bit of a personality. If you love that fresh-out-of-the-earth smell or the scent of a field after rain (with a hint of campfire in the distance), vetiver will make your heart sing.

Patchouli

Time to talk about patchouli – arguably one of the most misunderstood yet essential base notes out there. Patchouli is a leafy herb from the mint family and its oil has a very distinct scent: earthy, camphorous, slightly sweet, and yes, a bit musty or “hippie-ish.” But patchouli is so much more than its counterculture rep. Historically, patchouli has been used in Eastern cultures for ages; in the 19th century, it was used to scent Indian shawls – traders packed cashmere shawls with dried patchouli leaves to keep moths away during shipping, and when Victorian ladies got a whiff, they associated that exotic earthy scent with luxurious imports. A shawl that didn’t smell of patchouli was even considered fake! Then patchouli became a fad in Europe too – until tastes changed and it fell out of favor, only to rise again in the swinging 60s. In perfumery, patchouli is a cornerstone of the “Chypre” and “Oriental” fragrance families. It provides a dark, woody-earthy foundation that pairs magically with things like bergamot and oakmoss (in chypres) or vanilla, labdanum, and spices (in orientals). Classic example: Coty Chypre (1917) and its progeny like Guerlain Mitsouko (1919) used patchouli & oakmoss to create that shadowy forest-floor dry down that feels sophisticated and mysterious. Modern hits like Chanel Coco Mademoiselle and Dior Miss Dior (2005 version) also pack a patchouli punch beneath their sweet florals, giving a certain “swagger” to otherwise girly notes. Good patchouli smells rich, damp, woody, a tad spicy and sweet – like the soil of an enchanted forest, or a well-worn leather jacket stored with herbs. Bad patchouli can smell like a mildewed attic. The difference is quality and blending. Culturally, aside from hippies, patchouli is used in incense and rituals in Asia (it’s considered grounding). As a base note, patchouli lasts ages and often is what you smell on your clothes the next day. It’s a love-it or hate-it note for some, but in fine fragrances it’s indispensable.

Vanilla

Sweet, cozy, and downright delicious – vanilla is perhaps the most universally adored base note. It’s so well-known as a flavor that we often forget it’s also a fragrance. Natural vanilla comes from the pods of the vanilla orchid; in perfumery, we also use vanillin (the primary aroma compound) and other synthetic vanilla-like notes to amplify that yummy sweetness. The scent of vanilla is warm, creamy, comforting like baked goods, but also with an exotic, spicy floral nuance, if it’s natural vanilla extract. Historically, vanilla was brought from Mexico to Europe in the 16th century and quickly became a hit for flavoring foods and perfumes. It was exotic and expensive. In perfumery, early iconic uses include Guerlain Jicky (1889), which shocked polite society by pairing a hefty dose of vanillin with lavender and civet; and later Guerlain Shalimar (1925), often hailed as the queen of vanilla fragrances – it drapes a velvety vanilla over smoky incense and bergamot, creating the template for “Oriental” perfumes. Culturally, vanilla has often been associated with love and aphrodisiac properties. Certainly, it’s one of the most “edible” smelling notes – hence all those dessert-like gourmand perfumes after Mugler Angel’s success. Beyond Shalimar, consider Tom Ford Tobacco Vanille (2007), which combines rich vanilla with tobacco and spices – it smells like a decadent holiday pipe smoke in a library with cookies baking somewhere. Or Comptoir Sud Pacifique Vanille Abricot, which is basically fruit vanilla sponge cake in a bottle. But vanilla isn’t only super-sweet; in Atelier Cologne Vanille Insensée, it’s surprisingly woody and light, showing versatility. It’s the ultimate comfort note and lets be honest: who doesn’t like the smell of vanilla?

Amber (and Ambroxan)

Amber is a bit of a misleading term in perfumery as it doesn’t refer to the fossilized tree resin or the gemstone, but an accord that traditionally combines resins like labdanum, benzoin, and vanilla to create a sweet, warm, golden scent. It’s the heart of many “oriental” perfumes. Historically, the concept of the amber accord came from mixing labdanum (a sticky resin from rockrose that smells sweet and leathery) with vanilla and often a dash of animalic notes, giving a sense of the fabled scent of ambergris. Classic amber-heavy perfumes include Ambre Sultan by Serge Lutens (2000), which is like pure amber decadence and wearing it feels like you’re in a North African market at sunset, surrounded by spice and incense vendors. Or The Merchant of Venice’s Amber Intense, which doubles down on the luxurious warmth. Guerlain’s Shalimar, previously mentioned, is also ambery at its base. Ambroxan also deserves a shout: it’s a synthetic molecule that emulates the scent of natural ambergris (a rare substance from sperm whales). Ambergris has a unique salty-sweet, oceanic woody smell that’s hard to describe but adds amazing depth. Ambroxan (and similar molecules like Cetalox) became super popular for imparting a modern, transparent amber/woody note with monster longevity. Case in point: Dior Sauvage (2015) anchors its fresh peppery top with a massive dose of Ambroxan, giving it that persistent, glowing “amber-wood” trail that you either love or have smelled on every guy within a 10-mile radius. Another is Juliette Has a Gun – Not a Perfume, which cheekily is just Cetalox (an ambroxan-type) as a single-note fragrance – minimalist, skin-like, and oddly addictive for some noses. Back to amber as a whole: amber is sensual and comforting at once – sweet but not bakery-sweet, warm like a hug, and slightly mysterious. When a perfume’s drydown is described as “ambery,” expect that golden glow enveloping you. And if you see “ambergris” in a note list these days, it’s almost always a synthetic like ambroxan (real ambergris is extremely scarce and expensive). Love it or find it in everything, amber in all forms is here to stay.

Musk

Once upon a time, “musk” meant a substance secreted from the musk deer’s gland (gross but true) which, when extremely diluted, gave an indescribably sensual, warm, skin-like scent. Real musk tincture was a cornerstone of perfumery for centuries – a fixative and aphrodisiac so prized it was literally worth more than gold. Fast forward to today: real deer musk is banned in most places and we have a whole zoo of synthetic musks (including white musks, macrocyclic musks, polycyclic musks) to replace it. When we say a perfume has “musk” notes now, it usually refers to these clean, soft musks that give a soapy and of powdery-sweet smell. Musk in the base is like an invisible hug that makes a scent feel rounded and linger in a subtle way. Culturally, musks have gone from raunchy (old animalic musks were potent and very sensual, even a tad dirty in smell) to squeaky clean (modern musks have more “fresh out of the shower” vibes). White Musk, for example, as popularized by The Body Shop’s iconic 1981 fragrance, is all gentle fluffy softness – no animal harm, just laundry-fresh allure. That became a huge trend; indeed, ask any ’90s teen about Body Shop White Musk and watch their eyes light with nostalgia. But not all modern musks are clean-clean; some like Kiehl’s Original Musk (which allegedly used a 1920s recipe) have a slightly dirtier, skin-like nuance beneath the soapy top. Musk is also interesting because some people can’t smell certain musks due to anosmia. Have you ever had a perfume that you go “this is weak” but others smell strongly? Possibly a musk anosmia at play. Famous musk-forward scents: Narciso Rodriguez For Her (2003) revolves around a radiant musk that’s both clean and sensual. Glossier You (2017) is basically a tribute to musk; it aims to smell like you but better, using modern subtle musks and a bit of iris and pepper. And of course, Musk by Jovan or Alyssa Ashley Musk – cheap thrills from the ’70s that were all about that naughty musk of yore. As a base note, musk’s main job is to make the fragrance last and feel like it melts with your skin. It’s the quiet anchor – you might not consciously pick it out, but when you think “Mmm, this perfume smells so good on my clothes even next day, kind of like me but just delightful,” that’s musk working its magic. In short, musk is the sensual cuddler of base notes: from dirty to laundry-clean, it runs the gamut, but always leaves an impression of human warmth.

Oakmoss

If you’ve ever worn a classic chypre perfume or a barbershop aftershave and felt a certain foresty, slightly dusty dryness at the end, you’ve met oakmoss. Oakmoss is a type of lichen that grows on oak trees (mostly in Europe), and in perfumery it provides a deeply earthy, woody, slightly damp green note. Think of the smell of a forest floor with moss and decaying leaves after rain – earthy yet slightly bitter-green and dry. Oakmoss has been a defining base note for the chypre family since François Coty’s Chypre (1917) made it famous by pairing bergamot, labdanum, and oakmoss. That combo created an addictive contrast of fresh top and dark base. Oakmoss gives incredible depth and a “classic” feel – Guerlain Mitsouko (1919), Dior Eau Sauvage (1966), Chanel No.19 (1970), Hermès Calèche (1961) – all had significant oakmoss in their original formulations, lending that characteristic elegant earthy finish. Culturally, oakmoss is almost synonymous with the golden age of perfumery; it’s what made so many vintage scents feel rich and sophisticated. However oakmoss contains molecules that can cause skin allergies in some people, and over the 21st century the EU and IFRA (the fragrance regulatory body) have placed heavy restrictions on its use. By 2010, most perfumes had to be reformulated to reduce real oakmoss or use a “deallergenic” version (oakmoss with atranol removed, if you want the technical detail). Many perfumers and enthusiasts lament that modern versions of classics are “thin” because of the reduction of oakmoss – indeed, Guerlain’s reformulation of Mitsouko, for instance, lost some of its moody oakmossy heft. But some oakmoss effect can be recreated with other notes or synthetics like Evernyl. In any case, what does it smell like in the base? It imparts an austere, slightly smoky and very “perfumey” dry down – in a good way. Two of my fragrances from my collection that prominently feature oakmoss are Hacivat by Nishane (2017) & Evernia by Ormonde Jayne (2021). Whenever you smell a fragrance that feels like walking through a wet forest in a rain jacket, you know that oakmoss is playing a part somewhere.

Leather

Leather is a beloved accord in perfumery that adds a distinctive animalic, smoky, sometimes bitter aroma. This one was originally hard for me to wrap my head around. Why would you want to smell like leather? It was a flanker of Halfeti, Halfeti Leather by Penhaligon’s (2020) fragrances out of the U.K. that changed my mind. Historically, perfumed leather was a thing since at least the 16th century: French glove makers in Grasse scented leather gloves for nobility (to mask the nasty tanning odors), giving birth to the idea of “leather notes” in perfumery. These were often created with birch tar, a smoky resin that smells like Russian leather (think campfire and cured hides), and quinolines, synthetic molecules that give a sharp old boot smell. Add in some animalics or florals to smooth, and voila – you’ve got leather. Classic leather perfumes include Cuir de Russie by Chanel (1924) – inspired by Russian leather boots, it’s smoky, dark, yet refined with flowers; it basically smells like a posh smoke-filled room where everyone’s in leather and furs. Then there’s Knize Ten (1924), an ultra-refined dry leather with a touch of citrus and florals – a benchmark masculine leather (the kind of scent James Bond might wear while driving an Aston Martin). Fast forward, Tom Ford Tuscan Leather (2007) became a modern icon, a smooth suede-like leather with raspberry hint and so renowned that Drake named a song after it. Leather can take many forms: Dior Fahrenheit has a gasoline-like violet-leather vibe; La Yuqawam by Rasasi is an unabashed Tuscan Leather clone beloved in Middle East; Memo Paris Irish Leather mixes green notes with a saddle leather; Hermès Kelly Calèche does a light floral leather, as if sniffing a Hermès purse interior with some leftover perfume. Cultural associations: leather in scent often connotes luxury, power, sometimes rebellion. There’s also a subset called “white leather” or “suede” notes that are softer and creamier – think Bottega Veneta (2011) where leather is polished and rounded by plum and patchouli, coming off like expensive suede heels rather than rawhide. As a base note, leather adds tremendous longevity and a statement – it’s not a shy note. You usually find it either as the main theme or not at all. When a perfume dries down with a leathery tone, it can feel elegant or provocatively smoky, depending on style. Love it or leave it, the smell of leather in perfume has an undeniable cool factor.

Oud (Agarwood)

In the realm of base notes, oud is the rockstar that went from Middle Eastern treasure to global sensation in the last couple of decades. Oud is a resinous wood from the Aquilaria tree infected by a certain mold – yes, it’s basically fungus-induced wood rot, but its a stink that has attracted thousands of fans over time. Natural oud oil (also called agarwood) is one of the most expensive perfumery materials and it’s been used in Middle Eastern and Asian cultures for centuries, both as incense and personal oil. The scent of oud is hard to describe if you haven’t smelled it: it’s deep, dark, and woody, but with facets that can be smoky, animalic (even bordering on barnyard or medicinal), and balsamic sweet all at once. Pioneers like Yves Saint Laurent M7 (2002) introduced oud to Western markets (albeit in a toned-down way). Then niche houses like Montale built entire lines around oud (Black Aoud is a legend among those). Soon every designer had their “oud” fragrance: Tom Ford’s Oud Wood (2007) made it ultra-chic (a smooth, sanitized oud for the masses – rich and woody without the funk); Armani Privé Oud Royal went full opulent; even Versace and Gucci hopped on (with varying success). Now, oud in Western perfumery is often rendered via synthetic approximations or a tiny bit of the real deal, tempered with rose, vanilla, or fruits to make it more approachable. A classic pairing from Middle Eastern tradition is Rose and Oud – the jammy sweetness of rose perfectly balances oud’s dark depth (ex: Maison Francis Kurkdjian Oud Satin Mood or By Kilian Rose Oud). There are also variations: Hindi ouds (from India) tend to be more barnyard-like and potent; Cambodi ouds sweeter and woody; Laos ouds green, etc. As a base note in your perfume, when oud is present, trust me, you’ll know it as well as everyone else around will know it as well. It anchors a scent with gravity and complexity like no other. It’s the kind of scent trail that leaves people intrigued or in awe. If you wear a fragrance with a strong oud base, be careful as oud can be challenging. Handle oud with confidence and it will reward you with a mystical aura worthy of a a cutting-edge fashion icon.

Tonka Bean (Coumarin)

Ever wonder what gives that delicious “almondy-vanilla with a hint of hay” whiff in some fragrances? Often it’s tonka bean – the seed of a South American tree – which is packed with coumarin, a naturally occurring compound that basically is the scent of tonka. Coumarin has a fascinating place in perfumery history: it was the first major synthetic fragrance compound used in a fine perfume, in Houbigant’s Fougère Royale (1882). That perfume launched the whole fougère/barbershop genre (aromatic “fern-like” scents with lavender, oakmoss, and coumarin) and effectively birthed modern perfumery as we know it, proving that lab-derived smells could elevate natural materials. So coumarin/tonka is kind of a big deal. The smell of tonka bean is cozy and inviting – imagine a mix of sweet vanilla, spicy almond (like cherry pit), and freshly mown hay with a hint of tobacco. It has a slightly powdery, heliotropic vibe (heliotrope flowers also smell of almond and cherry – that’s coumarin too). In the base, tonka adds a velvety warmth and helps “fix” a perfume like a less sugary alternative to straight vanilla. Many classic and modern perfumes use tonka to add that sweet, rounded caress in the drydown. For example, Guerlain Jicky (1889) and Guerlain Shalimar (1925) both feature coumarin alongside vanilla – part of why Guerlain’s signature “Guerlinade” base has that plush, sweet tonality. Fast forward, Dior Fahrenheit had tonka under its leather/violet, giving a subtly sweet finish; Hermès L’Ancienne Eau d’Orange Verte boosts the cologne with tonka to last longer. Tonka also shines in “gourmands” – e.g., Thierry Mugler AMen (1996) mixed coffee, tonka, vanilla, and patchouli into a literal sugar bomb for men; Dior Feve Delicieuse (2015) is basically a love letter to tonka, so rich and dessert-like you may gain weight by smelling it (not really, but it’s that sweet and buttery). From my collection, Myrrh & Tonka from Jo Malone London (2016) gets a lot of daily wear throughout the year. Outside the perfume nerd sphere, tonka is less known by name, but trust me, everyone has smelled it somewhere. As a base note, tonka/coumarin plays well with others: it can give a “bailey’s Irish cream” vibe with coffee notes, a “fresh bakery” touch with spices, or a “cozy cashmere” feel with woods. It’s often that extra something that makes you sniff your wrist and go “Mmm, something in this is addictive.” If vanilla is too straight-up sweet for your taste, tonka might be your jam.

Iso E Super (Woody Ambroxan Magic)

We’re getting a bit technical here, but Iso E Super has become so famous (or infamous) in perfume circles that it deserves a shoutout as a “note.” Iso E Super is a synthetic molecule, discovered in 1973 by IFF chemists, and while it’s not something you’ll find on a forest floor or spice rack, it’s everywhere in modern perfumery. Its scent is often described as a transparent, nebulous woody note like cedarwood, but softer and more ethereal, with a hint of amber and a velvety, almost phantom presence. On its own, some people can barely smell it, while others find it enveloping and delicious. It’s one of those “You’ll know it when you smell it” scents. Historically, Iso E Super was used in small amounts in the late ‘70s and ‘80s for a subtle wood lift. Then came Dior Fahrenheit (1988), which used an unprecedented dose (about 25% of the formula!) that gave Fahrenheit its distinctive, expansively woody aura that made it such a hit. Perfumers realized you could overdose Iso E Super and get this amazing radiance. Enter Giorgio Beverly Hills for Men (1984) and Lancôme Trésor (1990) which also used lots of Iso E. But the real cult following came with Escentric Molecules Molecule 01 (2006) – a fragrance composed of nothing but Iso E Super. People went nuts for it: some claim it’s a pheromone and that strangers compliment them like crazy; others can’t smell a darn thing and think it’s emperor’s new clothes. The truth is, Iso E Super does have a certain magic: it’s very smooth, woody, ambery, slightly musky, and tends to “vanish and reappear” – you go noseblind and then catch whiffs later unexpectedly. It also layers wonderfully with other scents. Culturally, the success of Molecule 01 turned a lot of everyday people into aware-ISO-sniffers. Now many people can notice the “pencil cedar/velvet wood” drydown in perfumes. If you’ve worn Juliette Has a Gun Not a Perfume (which is actually just Ambroxan) or Glossier You (heavy on ISO E and musk) or Terre d’Hermès, you’ve enjoyed this molecule. In perfumery, Iso E is often part of the “secret sauce” that makes a perfume have that lingering modern woody aura and great projection. As a base note, it’s like an amplifier: it boosts other notes, adds a comfy woody-amber cushion, and extends longevity. Be warned though, a small percentage of people can’t smell it well, and a smaller percentage might find it sour or sharp. But for most, it’s that subtle “I don’t know what’s so nice in the drydown, but it’s nice” element. When someone smells “modern and expensive-woody”, that’s probably Iso E Super doing what it does.

Conclusion

Whether you’re spraying on a zesty citrus that evaporates before lunch, a lush floral bouquet to get you through the afternoon, or a sultry mix of woods and musks that clings to your jacket for days, understanding perfume notes adds a whole new dimension to your fragrance experience. From the top notes that flirt and flee, to the heart notes that define your scent’s personality, to the base notes that whisper sweet nothings hours later, each note has its own story, history, and mood. And now, armed with this guide, you can impress your friends (or the sales associates) with everything you know about the olfactory wheel. In any case, the world of perfume notes is vast and wonderful and much like a great scent, it’s one part science, one part art, and a little dash of magic. So go forth, sniff bravely, and find those top/heart/base notes that sing to your nose. After all, the best perfume is the one that makes you feel like the main character of your own movie.